Software development is a crazy business. Every time you feel you’ve mastered a programming language or framework, it’s declared obsolete, and you’ve got to crawl your way back up a learning curve to master something new. These changes are never under your control—they are handed down from on high, from Apple, Microsoft, Google, Adobe, or whichever corporate tail it is that wags your particular dog. They make a change, and we scramble to adapt. You know, as if our livelihoods depended on it, or something.

I’m not exactly complaining, mind you, because there’s nothing I enjoy more than learning something new. But there are days when I wish I’d taken up, say, shoeing horses. There is no “Horseshoes 2.0” on the horizon.

If you’d like to follow along, you can find the project at:

https://www.siliconpublishing.com/resources/oleextensions/com.spi.basicCommunication.zip

For the Better…?

In the old days, before, say, 2009, a developer who wanted to develop a plug-in panel for InDesign would have to learn to set up their development environment to use the InDesign C++ SDK, then write and debug the code. This process could take weeks or months. Making the panel work in Illustrator would require the same process—install and study the SDK, write and debug the code, and install the plug-in. Want to add a panel for Photoshop? Repeat the process.

When I was working at Adobe, I helped (in a minor way) build the Creative Suite Extension Builder. CS Extension Builder gave developers a way to create add-ons for Creative Suite applications using Flex and Actionscript, rather than writing plug-ins in C++. Actionscript could connect to the scripting object model of the host application, with Flex providing the user interface controls. All of this was wrapped up in a neat package that you could install in FlashBuilder.

With the CS Extension Builder, you could build a working panel in about thirty seconds. In my opinion, it was one of the best third-party development tools ever created—and a testament to the skill and creativity of my hard-working teammates.

Imagine my surprise when, last September, Adobe announced that they would be discontinuing the CS Extension Builder and would replace it with a new development framework based on HTML and JavaScript. Instead of building your user interface in Flex, running inside a Flash window, you’ll use HTML and CSS, running in an embedded version of Google’s Chrome browser. This makes up part of Adobe’s Common Extensibility Platform—the other part is what we used to call “CSXS.” I’ll refer to this collection of technologies as “CEP” from here on out.

Imagine my further surprise when I found that the new system was not even close to replacing CS Extension Builder. Key capabilities were missing. The documentation was thin, and very few example projects were available.

Not only that—we don’t have a choice. SPI’s CS Extensions for InDesign are literally going to stop working in the near future. This includes the Template Editor, a key part of the Silicon Designer workflow, and a very large hunk of code. Some of our other extensions, such as Silicon Connector for Box, will need to be rewritten.

I think, at this point, that most Creative Suite third party developers went through the classic phases of grief and loss: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Coping with Change

I’ve only gotten to the “acceptance” stage very recently, myself—and that’s due to two factors: Not only have I had more time to work with HTML extensions, but the Adobe team has made great strides on the capabilities of the framework and have added more documentation and examples. The team has also started communicating more frequently—a critical, if often overlooked, part of any third-party developer infrastructure. Communication is actually more important than development when you’re in this role.

There was nothing to do, therefore, but to get started. What did we need to do in order to move our CS Extensions to the new world? In CS Extension Builder, we could use Actionscript to call into the scripting object model of the application, and respond to application events directly. In a CC extension, HTML and JavaScript run the user interface, while most of the work inside the application takes place in ExtendScript.

Given this, we needed to know how to:

- Call ExtendScript functions from JavaScript.

- Send data from JavaScript to ExtendScript.

- Get data back from ExtendScript.

- Send application events from ExtendScript to JavaScript.

By writing examples, and by studying what others had written, I convinced myself that the new system could handle the first three points when working with InDesign. The last point, however, was almost a show-stopper—if you want to create a user interface that responds to changes in the InDesign document, you’ve got to be able to monitor key application events, such as Application.AFTER_SELECTION_CHANGED.

The CC extension framework supports a small number of common Adobe application events: documentAfterActivate, documentAfterDeactivate, documentAfterSave, applicationBeforeQuit, and applicationActivate. As you can probably guess from the event names, they’re of limited use in finding out what’s going on inside an InDesign document.

Then, literally last week as I write this, Adobe released an external library that makes the remaining point possible in InDesign.

A Very Simple Example InDesign Extension

First, you’ll need to set up your extension’s folder structure. David Deraedt has created extensions for Brackets and Sublime Text that will do this for you (see “Resources,” later in this post), but I’m not going to do that—though I do use Brackets for my extension development. I have a template that I like to use for simple HTML extensions, and I just make a duplicate of it whenever I want to create a new one. I have a different, more complex template that I use when I create a template that uses the Angular.js framework, but that’s a topic for a future post.

You’ll notice two things about the template, right away:

- I have included the library json2.js in the “libraries” folder inside the “jsx” folder. This library provides support for JSON (a way to converting strings to JavaScript objects and back again). It’s very useful for passing data back and forth between the ExtendScript (jsx) and JavaScript (js) sides of the extension. We need this, because we cannot send “live” ExtendScript objects to JavaScript, as would could with Actionscript.

- I have included the PlugPlugExternalObject library in the “jsx” folder. This ExtendScript library makes it possible to send events from the InDesign’s ExtendScript object model to the JavaScript side of the extension. We’ll use this to send events when InDesign application-side events fire.

Apart from the above, everything else should be straightforward—JavaScript files go in the “js” folder; ExtendScript files go into the “jsx” folder, css files are found in the “css” folder, and so on. For both JavaScript and ExtendScript, libraries we’ll be working with go in the “libraries” folders found inside those folders. Our main HTML file is, as you’d expect, “index.html.”

A couple of notes about the above file structure:

- I’ve turned on “show hidden files” so that you can see the .debug file.

- The file “CSInterface-5.0.0.js” is the file that’s normally named “CSInterface.js.” I changed the name so that I can differentiate between CEP 5.x and CEP 4.x versions of the library (at some point, I may have to develop for the 2013 version of CC, which uses CEP 4.x).

- Don’t worry about the icon files—I may deal with icons and application themes in a future post. This extension doesn’t care about the application’s user interface theme.

This extension does a number of things:

- Shows how to communicate between JavaScript and ExtendScript, in four key ways (as I mentioned earlier).

- Watches the selection InDesign, and, if and when a page item is selected, displays the stroke weight, stroke color, and fill color of the page item in the panel.

- Sets the stroke weight, stroke color, and fill color of a selected page item from settings in the user interface of the panel.

- Displays a list of event messages as they occur.

First, take a look at the “.debug” file for the project. Note that we’re not going to go through the steps of packaging this extension as a ZXP—we’re going to run it in debug mode. To get that set up, you’ll need the Google Chrome browser (if you don’t’ have it already) and you’ll need to work through the steps in the Adobe Application Extension SDK (aka CC14_Extension_SDK.pdf—see the “Resources” section later in this post). Once the extension folder is in the right place (again, refer to the PDF for the location on your specific platform), it’ll appear on the Window>Extensions menu as soon as you restart InDesign.

In the .debug file, note the name of the extension package (whatever you named the folder when you copied the template) and the extension ID you want to use for debugging. These are the two bits of text you’ll need to change when you get to the point of making your own extension from this template.

Next, take a look at the manifest.xml file inside the “CSXS” folder. This is the file that tells CEP what the extension is and where to find its various parts. If you’re using this template, there are five text changes (three of one sort; two of another). They’re highlighted in the markup below.

Note the <MainPath> and <ScriptPath> elements—these tell CEP where to find the main HTML and ExtendScript files for your extension. You’ll need to change this if you decide to change the name of either or both of the files in the template.

From CEP’s point of view, that’s all you need to create a new extension. It should be obvious that the index.html file needs to contain references to your JavaScript file (I strongly advocate using an external file, rather than writing your JavaScript inside the HTML) and any libraries you need to load.

I’m not going to walk through the JavaScript and ExtendScript code in this extension. I think it’s reasonably well-commented, and should be pretty easy to understand. Note that, in some cases, I have intentionally resisted the urge to refactor the code for efficiency—my idea is to make it easier to follow. A production version of this script would probably remove a lot of duplicated code (I’d probably use a single function for setting up event listeners, for example).

I do want to call attention to the tag-team between JavaScript and ExtendScript in getting the PlugPlugExternalObject library set up. On the JavaScript side, I use CEP to determine which version of the library should be loaded (Mac OS or Windows; 32-bit or 64-bit), then pass the library file location to ExtendScript. Loading this library is critical, because it gives us a way to respond to InDesign’s application-specific events. To do this, we rely on the getOSInformation() method of the CSInterface object.

Put the extension folder in the correct folder on your system (again, refer to the Adobe PDF for where that is), then:

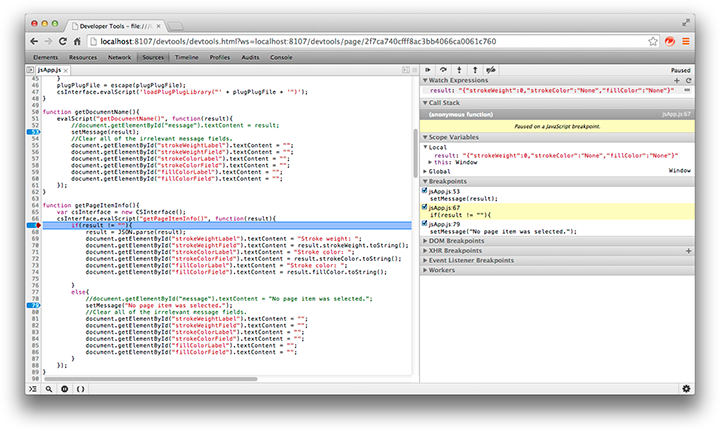

- Start Chrome and point it at the port we assigned in the .debug file (8107, unless you’ve changed it). After the page loads, and before you do anything else, check the Console tab to verify that your extension loaded without an error (you’ll see an error message here, in red, if something happened as InDesign tried to load the extension).

- Click the Sources tab. If necessary, locate and select your JavaScript file. Once the file is open in the Sources tab, you can place breakpoints in the JavaScript source where you’d like to observe variables or step through lines of code.

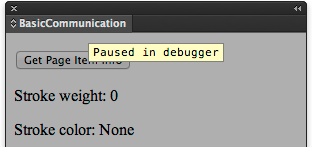

- Return to InDesign and play with the extension. When you hit a breakpoint, “Stopped in Debugger” will appear in your panel.

You don’t have to quit and restart InDesign every time you make a change to the source code of the extension. All you need to do is close and re-open the extension (restarting your Chrome debugging session, if necessary). This is actually a better debugging workflow than we had in the CS Extension builder.

Tips and Tricks

A few, entirely personal, thoughts and observations on CEP extensions (your mileage may vary):

- As I mentioned above, once you have debugging set up, you won’t need to restart InDesign every time you change the code in your extension. Changing the HTML markup, however, sometimes requires a restart. Mistakes in manifest.xml (forgetting to change the ExtensionBundleName attribute, for example) will sometimes require that you reset InDesign’s preferences.

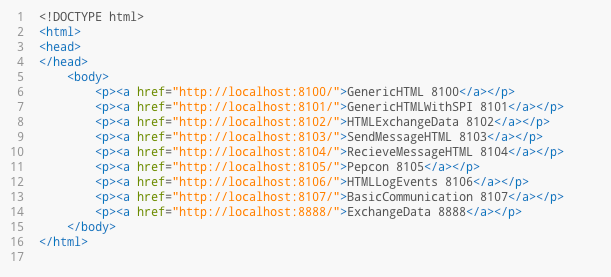

- Keep an HTML page somewhere on your system that contains links to the extensions you want to debug. This way, you can open it in Chrome and click the link for the extension you want to work with, rather than having to remember and re-type the number you assigned it in the .debug file. I keep this file on my desktop, and have made it my Chrome home page.

- Don’t invest too much time or effort in using the Eclipse-based Extension Builder released via Adobe Labs. All of the signs point to Eclipse extensions being phased out in favor of lighter-weight text editors, such as Brackets or SublimeText (see “Resources,” below). Please don’t take this as any sort of official statement—I don’t work at Adobe, and I really have no idea what their plans are. At the moment, I’m using Brackets, and digging it.

- Edit your ExtendScripts in the ExtendScript Toolkit (ESTK). The ESTK is not perfect, but at least it can check your ExtendScript syntax (something you can’t do in, for example, Brackets or Sublime Text). You’ll need to debug and develop the ExtendScript part of your extension there, anyway.

- The PlugPlugExternalObject library can be used for things other than sending InDesign events to the JavaScript side of your extension. It can be used to send an event at any point in your ExtendScript code. This means that you could use it to update a progress bar monitoring a task that takes place in an ExtendScript loop, for example. At some point, probably later this year, I expect that the PlugPlugExternalObject library will be added to InDesign. At that point, you won’t have to include it with your extension.

- You can’t drop into debug mode in the ESTK from an ExtendScript function that’s called by JavaScript, even if the debugging target in the ESTK is set to the instance of the extension. I think that there might be a way to do this using app.doScript() to run a script file, but I haven’t had a chance to explore that idea. Most of the time, I find it’s pretty easy to develop/debug the ExtendScript in the ESTK as I normally would. Once you’ve done that, any problems you run into will be due to the way your JavaScript is sending parameters to the ExtendScript functions—and you can usually use the Chrome debugger to look at the parameters before they’re sent.

Trips and Tics

Some relatively standard HTML techniques/features don’t work in CEP. Here are a couple I’ve found:

- Want to have a tool tip pop up over an image? In “normal” HTML, you’d add text to the title attribute. In some browsers, the altText attribute will also work. Not in CEP. You’ll have to add the tool tip some other way (via CSS, for example).

- Adding an array as a datalist for an input field doesn’t work.

There may be others. To test, try opening your index.html (or whatever you’ve named your base HTML file) in Google Chrome. If something works there, but doesn’t work in your extension, you’ve identified a limitation of CEP.

Resources

Download the sample project discussed in this post here:

https://www.siliconpublishing.com/resources/oleextensions/com.spi.basicCommunication.zip

You can find the Adobe CEP resources and documentation here (Adobe links tend to change frequently, but these should be good for a bit after this piece is posted):

http://adobe-cep.github.io/CEP-Resources/

Go to the section “For developing CEP5 HTML/JavaScript extensions for CC2014 host applications”—this will get you to the documentation and the samples.

The PlugPlugExternalObject library is here (it’s also included in the sample project):

https://github.com/Adobe-CEP/CEP-Resources/releases/tag/1

I use Brackets as my source editor for everything other than ExtendScript. You can find more about it here:

Sublime Text is another editor, and it looks pretty great. I haven’t tried it yet:

David Deraedt has built extensions for Brackets and Sublime Text:

https://github.com/davidderaedt/CC-Extension-Builder-for-Brackets

https://github.com/davidderaedt/CC-Extension-Builder-for-Sublime-Text

Davide Barranca has created some excellent posts on CC extensibility (they’re for Photoshop, but most of the information also applies to InDesign):

http://www.davidebarranca.com/category/code/html-panels/